By Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D.

There has been a great deal of discussion recently — much of it fraught with frustration — about the challenges facing our nation’s academic communities: How do we support basic curiosity-driven research and maintain our position as the global leader in innovation and technology at a time of rapidly dwindling government funds? This dilemma was at the heart of a workshop convened by the National Academies that I attended in September in Washington.

One potential solution, much discussed at the conference, is through the creation of a new model of transdisciplinary research that pulls together investigators from many disciplines to focus, or converge, on high-value, near-term goals. This excites the industrial sector because it generates information that can more quickly translate into commercial innovation, but many people in the scientific community are frankly terrified by this approach. They feel that focusing on solving specific problems in the short term could steal funds from fundamental, investigator-driven research that delves into new terrain — essentially, the scientific equivalent of Captain Kirk’s “final frontier” — and which often uncovers high-value problems and solutions that no one knew existed.

There is a solution to this conundrum. I serve as founding director of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, which develops engineering innovations by emulating how nature builds. With support from a major philanthropic gift, and from visionary leadership at Harvard and our affiliated hospitals and universities, we developed a new model of innovation, collaboration, and technology translation that has attracted more than $125-million in research support from federal agencies, private foundations, and for-profit companies.

With 18 core and 11 associate faculty members, we have produced more than 625 publications, 600 patent applications, scores of corporate collaborations, several start-ups, and two human clinical trials over the past four and a half years.

How do we do this? Our approach is simple: We empower our individual scientists and engineers to turn their vision-inspired research into practical solutions to real-world problems. We give them the resources they need to translate their basic research into technologies and then help them to develop those technologies into commercially viable products and therapies. We do this by introducing scientists and engineers with extensive industrial experience in goal-oriented product development into key positions in our academic-research teams. Experienced business-development staff members, working with the university’s Office of Technology Development, also help coordinate these efforts and develop meaningful alliances with major industrial partners and corporate investors.

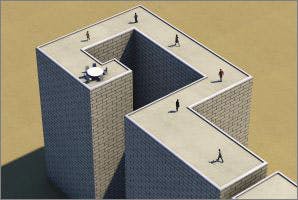

How can such an approach succeed in an academic empire composed of fiefdoms headed by entrepreneurial faculty who guard their territories with their lives? Our core faculty members, who are drawn from universities and hospitals across the Greater Boston area, maintain labs at their home institutions. But they know that if they want a seat at the round table of the institute, they must leave their personal agendas at the door and agree to participate in the collaborative culture for the benefit of all. Our research space is not allocated to individual faculty but rather organized as “collaboratories,” each of which is linked to a problem-oriented project.

We have also discarded the conventional model of grant reviews to distribute funds to our members. Instead we divide a portion of our funds among individual faculty members, which gives them and their students and fellows complete creative freedom. We then funnel a much larger investment into “enabling technology platforms,” each devoted to exploring a new high-risk research area. These platforms — consisting of faculty, technical staff, students, fellows, clinicians, and collaborators — build upon the brilliant advances that emerge from individual faculty labs to develop new breakthrough technological capabilities. In the end, it is always people who lead to innovation, not grant proposals or committees. So we invest in people.

Our nation desperately wants solutions to pressing health, environmental, and social problems and so, understandably, the impulse in Congress is to direct resources to goal-oriented, convergent research. But this leaves basic-science investigators in a quandary: Does the funneling of research dollars mean a temporary refocusing of investment or a catastrophic long-term shift toward a new mode of funding that will lead to their extinction? The latter is not a viable investment strategy for the continued growth of the economy.

Very simply, for the country to remain at the helm of innovation, it must persuade its best minds to continue thinking and discovering. It must provide funds to nurture their vision-inspired research — to pump the idea pipeline — while simultaneously investing in the kind of convergent, problem-oriented approaches that will turn basic discoveries into transformative technologies and commercially viable products. Only then will we be able to steer our national Enterprise to go where it has never gone before.