As we shift from carrying electronic devices in our pockets and purses to wearing them on our bodies, those devices need to be able to move and stretch with us, and to sense our movements in order to better do so. Such sensors must remain functional when stretched to several times their resting length, resist permanent deformation over the course of repeated stretching, and not impede the wearer’s natural movements. Multiple different types of sensors have been developed to try to meet this need, but none of them retain their function at strains of over 100%.

Wyss Institute researchers have created a sensor that can detect strain, pressure, and shear up to ~250% strain when embedded in an artificial “skin” made of highly stretchable silicone rubber. The sensor itself is composed of eutectic gallium–indium (eGaIn), a conductive liquid that is injected into microchannels arranged in three parallel layers of bonded silicone. When the silicone is deformed, the electrical resistance between the microchannels changes due to their reduced cross-sectional areas, increased channel lengths, or both. Using the combination of the signals from the three sensors, the device is able to detect the magnitude of and distinguish between three different stimuli: x-axis strain, y-axis strain, and z-axis pressure.

This technology has the potential to enable machines to sense their physical environment, similar to how our own skin mediates our interactions with the world.

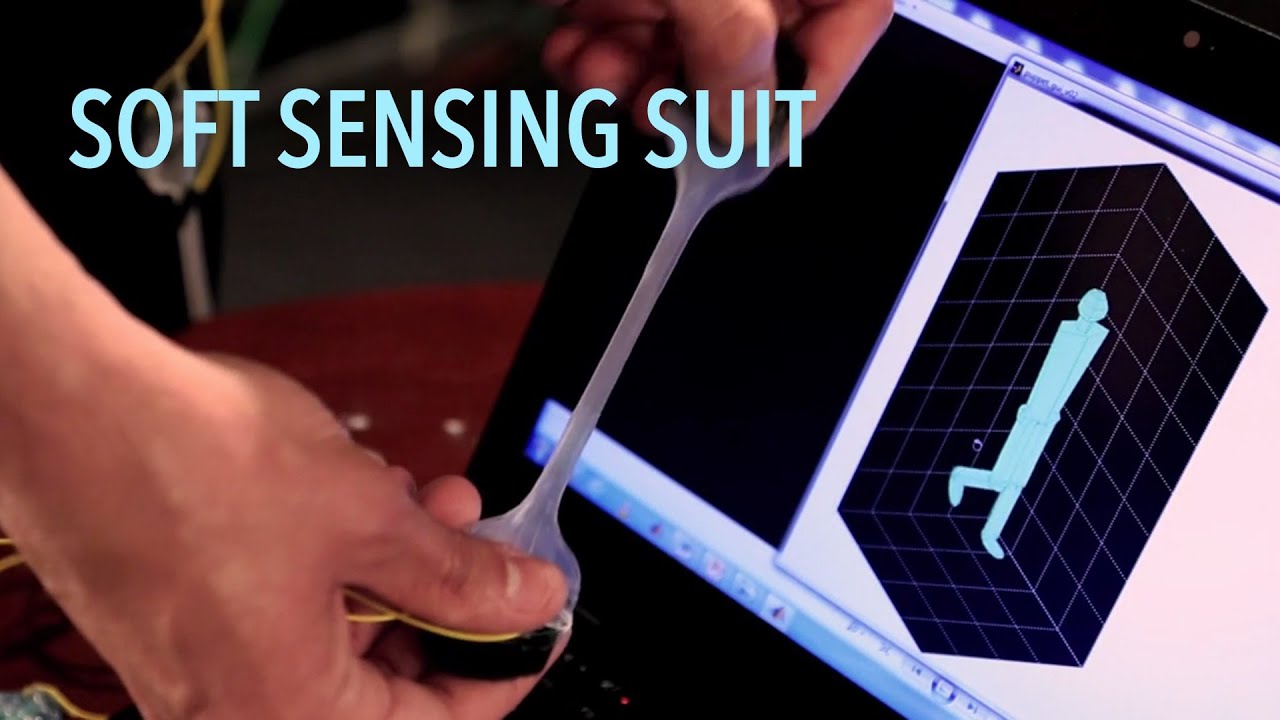

Applications of this technology may include artificial skins for humanoid robots, robotic prosthetics, soft wearable robots, human-friendly robots for human-robot interactions, and human-computer interfaces (HCI). Furthermore, due to the highly flexible and stretchable properties and thin form-factor, this soft skin technology can be directly integrated with any type of soft actuator.

This technology is undergoing further development. Some elements of the eGaIn sensors are available for licensing.