Biocompatible material is much tougher than cartilage

Cambridge, Mass. — A team of experts in mechanics, materials science, and tissue engineering have created an extremely stretchy and tough gel that may pave the way to replacing damaged cartilage in human joints.

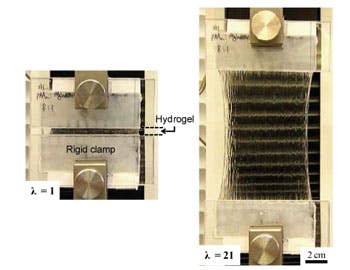

Called a hydrogel, because its main ingredient is water, the new material is a hybrid of two weak gels that combine to create something much stronger. Not only can this new gel stretch to 21 times its original length, but it is also exceptionally tough, self-healing, and biocompatible — a valuable collection of attributes that opens up new opportunities in medicine and tissue engineering.

The material, its properties, and a simple method of synthesis are described in the September 6 issue of Nature.

“Conventional hydrogels are very weak and brittle — imagine a spoon breaking through jelly,” explains lead authorJeong-Yun Sun, a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). “But because they are water-based and biocompatible, people would like to use them for some very challenging applications like artificial cartilage or spinal disks. For a gel to work in those settings, it has to be able to stretch and expand under compression and tension without breaking.”

Sun and his coauthors were led by three faculty members: Zhigang Suo, Allen E. and Marilyn M. Puckett Professor of Mechanics and Materials at SEAS and a Kavli Scholar at the Kavli Institute for Bionano Science and Technology at Harvard; Joost J. Vlassak, Gordon McKay Professor of Materials Engineering and an Area Dean at SEAS; and David J. Mooney, a Core Faculty Member at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard and Robert P. Pinkas Family Professor of Bioengineering at SEAS.

To create the tough new hydrogel, they combined two common polymers. The primary component is polyacrylamide, known for its use in soft contact lenses and as the electrophoresis gel that separates DNA fragments in biology labs; the second component is alginate, a seaweed extract that is frequently used to thicken food.

Separately, these gels are both quite weak — alginate, for instance, can stretch to only 1.2 times its length before it breaks. Combined in an 8:1 ratio, however, the two polymers form a complex network of crosslinked chains that reinforce one another. The chemical structure of this network allows the molecules to pull apart very slightly over a large area instead of allowing the gel to crack.

The alginate portion of the gel consists of polymer chains that form weak ionic bonds with one another, capturing calcium ions (added to the water) in the process. When the gel is stretched, some of these bonds between chains break — or “unzip,” as the researchers put it–releasing the calcium. As a result, the gel expands slightly, but the polymer chains themselves remain intact. Meanwhile, the polyacrylamide chains form a grid-like structure that bonds covalently (very tightly) with the alginate chains.

Therefore, if the gel acquires a tiny crack as it stretches, the polyacrylamide grid helps to spread the pulling force over a large area, tugging on the alginate’s ionic bonds and unzipping them here and there. The research team showed that even with a huge crack, a critically large hole, the hybrid gel can still stretch to 17 times its initial length.

Importantly, the new hydrogel is capable of maintaining its elasticity and toughness over multiple stretches. Provided the gel has sometime to relax between stretches, the ionic bonds between the alginate and the calcium can “re-zip,” and the researchers have shown that this process can be accelerated by raising the ambient temperature.

The group’s combined expertise in mechanics, materials science, and bioengineering enabled the group to apply two concepts from mechanics — crack bridging and energy dissipation — to a new problem.

“The unusually high stretchability and toughness of this gel, along with recovery, are exciting,” says Suo. “Now that we’ve demonstrated that this is possible, we can use it as a model system for studying the mechanics of hydrogels further, and explore various applications.”

“It’s very promising,” Suo adds.

Beyond artificial cartilage, the researchers suggest that the new hydrogel could be used in soft robotics, optics, artificial muscle, as a tough protective covering for wounds, or “any other place where we need hydrogels of high stretchability and high toughness.”

Additional coauthors included Xuanhe Zhao, a former Ph.D. student and postdoc at SEAS, now a faculty member at Duke University; Widusha R. K. Illeperuma, a graduate student at SEAS; Ovijit Chaudhuri, a postdoc in Mooney’s lab; and Kyu Hwan Oh, Sun’s former adviser and a faculty member at Seoul National University in Korea.

This work was supported by the U.S. Army Research Office, the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the National Institutes of Health, and the NSF-funded Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC) at Harvard. The researchersalso individually received support from the NSF Research Triangle MRSEC, a Haythornthwaite Research Initiation grant, the National Research Foundation of Korea, an Alexander von Humboldt Award, and Harvard University.